Introduction

A little over two years ago, I was working on Android for Beginners; a class that takes students from zero programming to their first Android app. As part of the course, students build a very simple one screen app called Court-Counter.

Court-Counter is a very straightforward app with buttons that modify a basketball score. The finished app has a bug though; if you rotate the phone, your current score will inexplicably disappear.

What’s going on? Rotating a device is one of a few configuration changes that an app can go through during its lifetime, including keyboard availability and changing the device’s language. All of these configuration changes cause the Activity to be torn down and recreated.

This behavior allows us to do things like use a landscape orientation specific layout when the device is rotated on its’ side. Unfortunately it can be a headache for new (and sometimes not so new) engineers to wrap their head around.

At Google I/O 2017, the Android Framework team introduced a new set of Architecture Components, one of which deals with this exact rotation issue.

The ViewModel class is designed to hold and manage UI-related data in a life-cycle conscious way. This allows data to survive configuration changes such as screen rotations.

This post is the first in a series exploring the ins and outs of ViewModel. In this post I’ll:

- Explain the basic need ViewModels fulfill

- Solve the rotation issue by changing the Court-Counter code to use a ViewModel

- Take a closer look at ViewModel and UI Component association

The underlying problem

The underlying challenge is that the Android Activity lifecycle has a lot of states and a single Activity might cycle through these different states many times due to configuration changes.

As an Activity is going through all of these states, you also might have transient UI data that you need to keep in memory. I’m going to define transient UI data as data needed for the UI. Examples include data the user enters, data generated during runtime, or data loaded from a database. This data could be bitmap images, a list of objects needed for a RecyclerView or, in this case, a basketball score.

Previously, you might have used [onRetainNonConfigurationInstance](https://developer.android.com/reference/android/app/Activity.html#onRetainNonConfigurationInstance()) to save this data during a configuration change and unpack it on the other end. But wouldn’t it be swell if your data didn’t need to know or manage what lifecycle state the Activity is in? Instead of having a variable like scoreTeamA within the Activity, and therefore tied to all the whims of the Activity lifecycle, what if that data was stored somewhere else, outside of the Activity? This is the purpose of the ViewModel class.

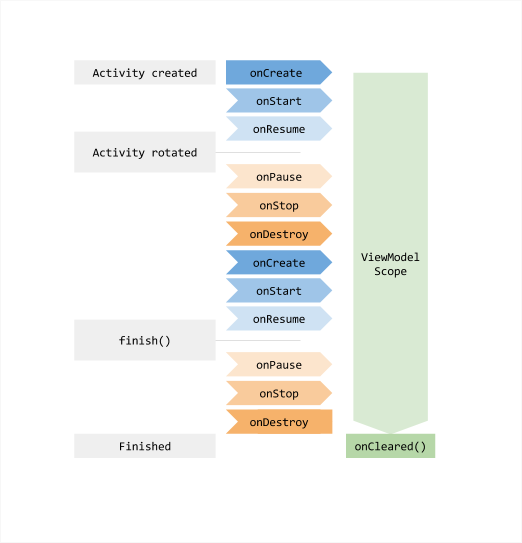

In the diagram below, you can see the lifecycle of an Activity which undergoes a rotation and then is finally finished. The lifetime of the ViewModel is shown next to the associated Activity lifecycle. Note that ViewModels can be easily used with both Fragments and Activities, which I’ll call UI controllers. This example focuses on Activities.

The ViewModel exists from when the you first request a ViewModel (usually in the onCreate the Activity) until the Activity is finished and destroyed. onCreate may be called several times during the life of an Activity, such as when the app is rotated, but the ViewModel survives throughout.

A very simple example

There are three steps to setting up and using a ViewModel:

- Separate out your data from your UI controller by creating a class that extends ViewModel

- Set up communications between your ViewModel and your UI controller

- Use your ViewModel in your UI controller

Step 1: Create a ViewModel class

Note: To create a ViewModel, you’ll first need to add the correct lifecycle dependency. See how here.

In general, you’ll make a ViewModel class for each screen in your app. This ViewModel class will hold all of the data associated with the screen and have getters and setters for the stored data. This separates the code to display the UI, which is implemented in your Activities and Fragments, from your data, which now lives in the ViewModel. So, let’s create a ViewModel class for the one screen in Court-Counter:

I’ve chosen to have the data stored as public members in my ScoreViewModel.java for brevity, but creating getters and setters to better encapsulate the data is a good idea.

Step 2: Associate the UI Controller and ViewModel

Your UI controller (aka Activity or Fragment) needs to know about your ViewModel. This is so your UI controller can display the data and update the data when UI interactions occur, such as pressing a button to increase a team’s score in Court-Counter.

ViewModels should not, though, hold a reference to Activities, Fragments, or Contexts.** Furthermore, ViewModels should not contain elements that contain references to UI controllers, such as Views, since this will create an indirect reference to a Context.

The reason you shouldn’t store these objects is that ViewModels outlive your specific UI controller instances — if you rotate an Activity three times, you have just created three different Activity instances, but you only have one ViewModel.

With that in mind, let’s create this UI controller/ViewModel association. You’ll want to create a member variable for your ViewModel in the UI Controller. Then in onCreate, you should call:

ViewModelProviders.of(**

In the case of Court-Counter, this looks like:

**Note: There’s one exception to the “no contexts in ViewModels” rule. Sometimes you might need an Application context (as opposed to an Activity context) for use with things like system services. Storing an Application context in a ViewModel is okay because an Application context is tied to the Application lifecycle. This is different from an Activity context, which is tied to the Activity lifecycle. In fact, if you need an Application context, you should extend AndroidViewModel which is simply a ViewModel that includes an Application reference.

Step 3: Use the ViewModel in your UI Controller

To access or change UI data, you can now use the data in your ViewModel. Here’s an example of the new onCreate method and a method for updating the score by adding one point to team A:

Pro tip: ViewModel also works very nicely with another Architecture Component, LiveData, which I won’t be exploring deeply in this series. The added bonus here of using LiveData is that it’s observable: it can trigger UI updates when the data changes. You can learn more about LiveData here.

A closer look at ViewModelsProviders.of

The first time the [ViewModelProviders.of](https://developer.android.com/reference/android/arch/lifecycle/ViewModelProviders.html#of(android.support.v4.app.Fragment)) method is called by MainActivity, it creates a new ViewModel instance. When this method is called again, which happens whenever onCreate is called, it will return the pre-existing ViewModel associated with the specific Court-Counter MainActivity. This is what preserves the data.

This works only if you pass in the correct UI controller as the first argument. While you should never store a UI controller inside of a ViewModel, the ViewModel class does keep track of the associations between ViewModel and UI controller instance behind the scenes, using the UI controller you pass in as the first argument.

ViewModelProviders.of(**

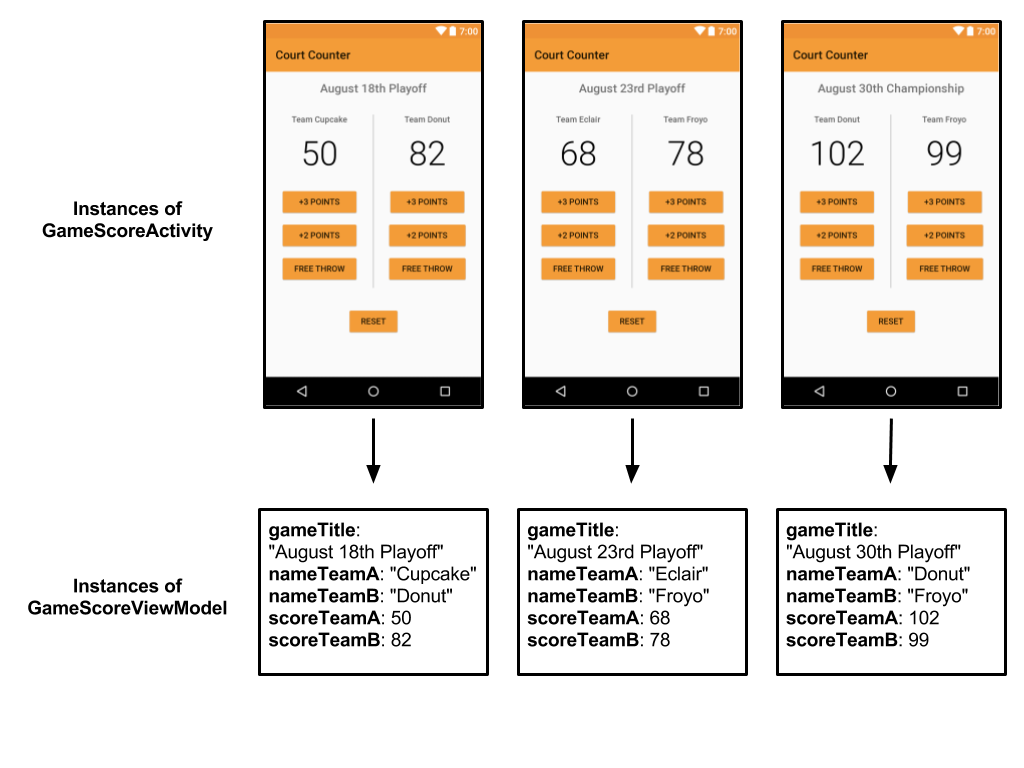

This allows you to have an app that opens a lot of different instances of the same Activity or Fragment, but with different ViewModel information. Let’s imagine if we extended our Court-Counter example to have the scores for multiple basketball games. The games are presented in a list, and then clicking on a game in the list opens a screen that looks like our current MainActivity, but which I’ll call GameScoreActivity.

For every different game screen you open, if you associate the ViewModel and GameScoreActivity in onCreate, it will create a different ViewModel instance. If you rotate one of these screens, the connection to the same ViewModel is maintained.

All of this logic is done for you by calling ViewModelProviders.of(<Your UI controller>).get(<Your ViewModel>.class). So as long as you pass in the correct instance of a UI controller, it just works.

A final thought: ViewModels are very nifty for separating out your UI controller code from the data which fills your UI. That said, they are not a cure all for data persistence and saving app state. In the next post I’ll explore the subtler interactions of the Activity lifecycle with ViewModels and how ViewModels compare to onSaveInstanceState.

Conclusion and further learning

In this post, I explored the very basics of the new ViewModel class. The key takeaways are:

- The ViewModel class is designed to hold and manage UI-related data in a life-cycle conscious way. This allows data to survive configuration changes such as screen rotations.

- ViewModels separate UI implementation from your app’s data.

- In general, if a screen in your app has transient data, you should create a separate ViewModel for that screen’s data.

- The lifecycle of a ViewModel extends from when the associated UI controller is first created, till it is completely destroyed.

- Never store a UI controller or Context directly or indirectly in a ViewModel. This includes storing a View in a ViewModel. Direct or indirect references to UI controllers defeat the purpose of separating the UI from the data and can lead to memory leaks.

- ViewModel objects will often store LiveData objects, which you can learn more about here.

- The ViewModelProviders.of method keeps track of what UI controller the ViewModel is associated with via the UI controller that is passed in as an argument.

Want more ViewModel-ly goodness? Check out:

- Instructions for adding the gradle dependencies

- ViewModel documentation

- Guided ViewModel practice with the Room with a View and Lifecycles Codelab

The Architecture Components were created based upon your feedback. If you have questions or comments about ViewModel or any of the architecture components, check out our feedback page. Questions about or suggestion for this series? Leave a comment!