Dependency injection in Android

Dependency injection (DI) is a technique widely used in programming and well suited to Android development. By following the principles of DI, you lay the groundwork for good app architecture.

Implementing dependency injection provides you with the following advantages:

- Reusability of code

- Ease of refactoring

- Ease of testing

Fundamentals of dependency injection

Before covering dependency injection in Android specifically, this page provides a more general overview of how dependency injection works.

What is dependency injection?

Classes often require references to other classes. For example, a Car class might need a reference to an Engine class. These required classes are called dependencies, and in this example the Car class is dependent on having an instance of the Engine class to run.

There are three ways for a class to get an object it needs:

- The class constructs the dependency it needs. In the example above,

Carwould create and initialize its own instance ofEngine. - Grab it from somewhere else. Some Android APIs, such as

Contextgetters andgetSystemService(), work this way. - Have it supplied as a parameter. The app can provide these dependencies when the class is constructed or pass them in to the functions that need each dependency. In the example above, the

Carconstructor would receiveEngineas a parameter.

The third option is dependency injection! With this approach you take the dependencies of a class and provide them rather than having the class instance obtain them itself.

Here’s an example. Without dependency injection, representing a Car that creates its own Engine dependency in code looks like this:

class Car {

private val engine = Engine()

fun start() {

engine.start()

}

}

fun main(args: Array) {

val car = Car()

car.start()

}

This is not an example of dependency injection because the Car class is constructing its own Engine. This can be problematic because:

-

CarandEngineare tightly coupled - an instance ofCaruses one type ofEngine, and no subclasses or alternative implementations can easily be used. If theCarwere to construct its ownEngine, you would have to create two types ofCarinstead of just reusing the sameCarfor engines of typeGasandElectric. -

The hard dependency on

Enginemakes testing more difficult.Caruses a real instance ofEngine, thus preventing you from using a test double to modifyEnginefor different test cases.

What does the code look like with dependency injection? Instead of each instance of Car constructing its own Engine object on initialization, it receives an Engine object as a parameter in its constructor:

class Car(private val engine: Engine) {

fun start() {

engine.start()

}

}

fun main(args: Array) {

val engine = Engine()

val car = Car(engine)

car.start()

}

The main function uses Car. Because Car depends on Engine, the app creates an instance of Engine and then uses it to construct an instance of Car. The benefits of this DI-based approach are:

-

Reusability of

Car. You can pass in different implementations ofEnginetoCar. For example, you might define a new subclass ofEnginecalledElectricEnginethat you wantCarto use. If you use DI, all you need to do is pass in an instance of the updatedElectricEnginesubclass, andCarstill works without any further changes. -

Easy testing of

Car. You can pass in test doubles to test your different scenarios. For example, you might create a test double ofEnginecalledFakeEngineand configure it for different tests.

There are two major ways to do dependency injection in Android:

-

Constructor Injection. This is the way described above. You pass the dependencies of a class to its constructor.

-

Field Injection (or Setter Injection). Certain Android framework classes such as activities and fragments are instantiated by the system, so constructor injection is not possible. With field injection, dependencies are instantiated after the class is created. The code would look like this:

class Car {

lateinit var engine: Engine

fun start() {

engine.start()

}

}

fun main(args: Array) {

val car = Car()

car.engine = Engine()

car.start()

}

Note: Dependency injection is based on the Inversion of Control principle in which generic code controls the execution of specific code.

Automated dependency injection

In the previous example, you created, provided, and managed the dependencies of the different classes yourself, without relying on a library. This is called dependency injection by hand, or manual dependency injection. In the Car example, there was only one dependency, but more dependencies and classes can make manual injection of dependencies more tedious. Manual dependency injection also presents several problems:

-

For big apps, taking all the dependencies and connecting them correctly can require a large amount of boilerplate code. In a multi-layered architecture, in order to create an object for a top layer, you have to provide all the dependencies of the layers below it. As a concrete example, to build a real car you might need an engine, a transmission, a chassis, and other parts; and an engine in turn needs cylinders and spark plugs.

-

When you’re not able to construct dependencies before passing them in — for example when using lazy initializations or scoping objects to flows of your app — you need to write and maintain a custom container (or graph of dependencies) that manages the lifetimes of your dependencies in memory.

There are libraries that solve this problem by automating the process of creating and providing dependencies. They fit into two categories:

-

Reflection-based solutions that connect dependencies at runtime.

-

Static solutions that generate the code to connect dependencies at compile time.

Dagger is a popular dependency injection library for Java, Kotlin, and Android that is maintained by Google. Dagger facilitates using DI in your app by creating and managing the graph of dependencies for you. It provides fully static and compile-time dependencies addressing many of the development and performance issues of reflection-based solutions such as Guice.

Alternatives to dependency injection

An alternative to dependency injection is using a service locator. The service locator design pattern also improves decoupling of classes from concrete dependencies. You create a class known as the service locator that creates and stores dependencies and then provides those dependencies on demand.

object ServiceLocator {

fun getEngine(): Engine = Engine()

}

class Car {

private val engine = ServiceLocator.getEngine()

fun start() {

engine.start()

}

}

fun main(args: Array) {

val car = Car()

car.start()

}

The service locator pattern is different from dependency injection in the way the elements are consumed. With the service locator pattern, classes have control and ask for objects to be injected; with dependency injection, the app has control and proactively injects the required objects.

Compared to dependency injection:

-

The collection of dependencies required by a service locator makes code harder to test because all the tests have to interact with the same global service locator.

-

Dependencies are encoded in the class implementation, not in the API surface. As a result, it’s harder to know what a class needs from the outside. As a result, changes to

Caror the dependencies available in the service locator might result in runtime or test failures by causing references to fail. -

Managing lifetimes of objects is more difficult if you want to scope to anything other than the lifetime of the entire app.

Choosing the right technique for your app

As demonstrated above, there are several different techniques for managing your app’s dependencies:

Manual dependency injection only makes sense for a relatively small app because it scales poorly. When the project becomes larger, passing objects requires a lot of boilerplate code.

Service locators start with relatively little boilerplate code, but also scale poorly. Furthermore, testing becomes more difficult because they rely on a singleton object.

Dagger is built to scale. It is well suited for building complex apps.

If your small app seems likely to grow, you should consider migrating to Dagger early when there isn’t as much code to change.

What’s the size of your project? For the purpose of deciding which technique to use, you can use the number of screens to proxy app size. However, note that number of screens is just one of many factors that can influence your app size.

Choosing the right technique for your library

If you’re developing an external SDK or library, you should choose between manual DI or Dagger depending on the size of the SDK or library. Note that if you use a third-party library to do dependency injection, your library is likely to increase in size.

Conclusion

Dependency injection provides your app with the following advantages:

-

Reusability of classes and decoupling of dependencies: It’s easier to swap out implementations of a dependency. Code reuse is improved because of inversion of control, and classes no longer control how their dependencies are created, but instead work with any configuration.

-

Ease of refactoring: The dependencies become a verifiable part of the API surface, so they can be checked at object-creation time or at compile time rather than being hidden as implementation details.

-

Ease of testing: A class doesn’t manage its dependencies, so when you’re testing it, you can pass in different implementations to test all of your different cases.

To fully understand the benefits of dependency injection, you should try it manually in your app as shown in Manual dependency injection.

Additional resources

Dependency Injection - Wikipedia

Manual dependency injection

Android’s recommended app architecture encourages dividing your code into classes to benefit from separation of concerns, a principle where each class of the hierarchy has a single defined responsibility. This leads to more, smaller classes that need to be connected together to fulfill each other’s dependencies.

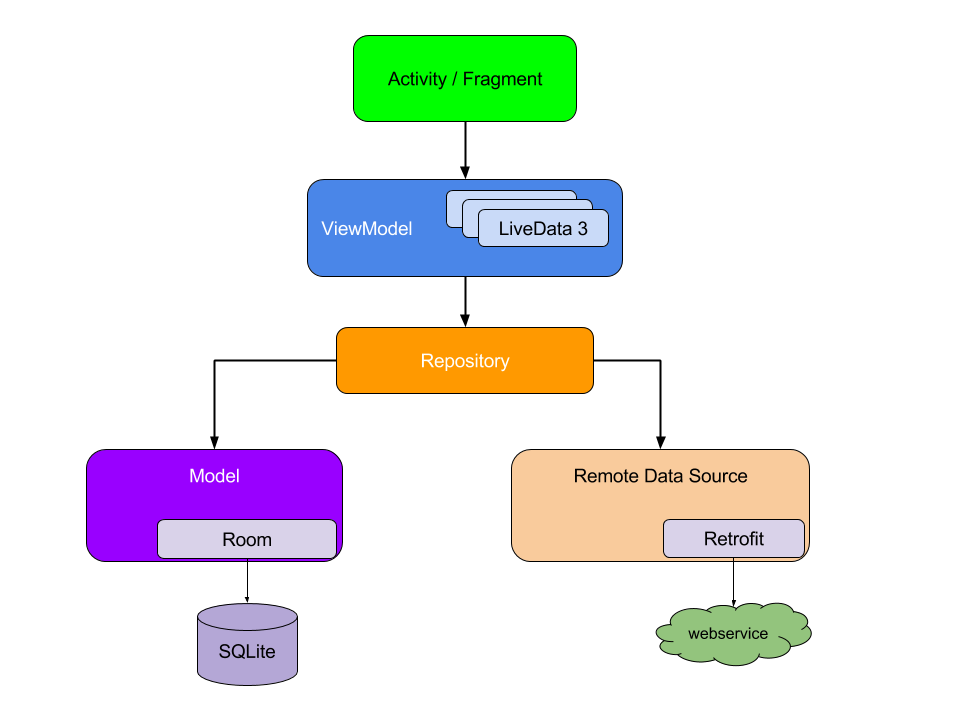

Figure 1. A model of an Android app’s application graph

The dependencies between classes can be represented as a graph, in which each class is connected to the classes it depends on. The representation of all your classes and their dependencies makes up the application graph. In figure 1, you can see an abstraction of the application graph. When class A (ViewModel) depends on class B (Repository), there’s a line that points from A to B representing that dependency.

Dependency injection helps make these connections and enables you to swap out implementations for testing. For example, when testing a ViewModel that depends on a repository, you can pass different implementations of Repository with either fakes or mocks to test the different cases.

Basics of manual dependency injection

This section covers how to apply manual dependency injection in a real Android app scenario. It walks through an iterated approach of how you might start using dependency injection in your app. The approach improves until it reaches a point that is very similar to what Dagger would automatically generate for you. For more information about Dagger, read Dagger basics.

Consider a flow to be a group of screens in your app that correspond to a feature. Login, registration, and checkout are all examples of flows.

When covering a login flow for a typical Android app, the LoginActivity depends on LoginViewModel, which in turn depends on UserRepository. Then UserRepository depends on a UserLocalDataSource and a UserRemoteDataSource, which in turn depends on a Retrofit service.

LoginActivity is the entry point to the login flow and the user interacts with the activity. Thus, LoginActivity needs to create the LoginViewModel with all its dependencies.

The Repository and DataSource classes of the flow look like this:

class UserRepository(

private val localDataSource: UserLocalDataSource,

private val remoteDataSource: UserRemoteDataSource

) { ... }

class UserLocalDataSource { ... }

class UserRemoteDataSource(

private val loginService: LoginRetrofitService

) { ... }

Here’s what LoginActivity looks like:

class LoginActivity: Activity() {

private lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// In order to satisfy the dependencies of LoginViewModel, you have to also

// satisfy the dependencies of all of its dependencies recursively.

// First, create retrofit which is the dependency of UserRemoteDataSource

val retrofit = Retrofit.Builder()

.baseUrl("https://example.com")

.build()

.create(LoginService::class.java)

// Then, satisfy the dependencies of UserRepository

val remoteDataSource = UserRemoteDataSource(retrofit)

val localDataSource = UserLocalDataSource()

// Now you can create an instance of UserRepository that LoginViewModel needs

val userRepository = UserRepository(localDataSource, remoteDataSource)

// Lastly, create an instance of LoginViewModel with userRepository

loginViewModel = LoginViewModel(userRepository)

}

}

There are issues with this approach:

-

There’s a lot of boilerplate code. If you wanted to create another instance of

LoginViewModelin another part of the code, you’d have code duplication. -

Dependencies have to be declared in order. You have to instantiate

UserRepositorybeforeLoginViewModelin order to create it. -

It’s difficult to reuse objects. If you wanted to reuse

UserRepositoryacross multiple features, you’d have to make it follow the singleton pattern. The singleton pattern makes testing more difficult because all tests share the same singleton instance.

Managing dependencies with a container

To solve the issue of reusing objects, you can create your own dependencies container class that you use to get dependencies. All instances provided by this container can be public. In the example, because you only need an instance of UserRepository, you can make its dependencies private with the option of making them public in the future if they need to be provided:

// Container of objects shared across the whole app

class AppContainer {

// Since you want to expose userRepository out of the container, you need to satisfy

// its dependencies as you did before

private val retrofit = Retrofit.Builder()

.baseUrl("https://example.com")

.build()

.create(LoginService::class.java)

private val remoteDataSource = UserRemoteDataSource(retrofit)

private val localDataSource = UserLocalDataSource()

// userRepository is not private; it'll be exposed

val userRepository = UserRepository(localDataSource, remoteDataSource)

}

Because these dependencies are used across the whole application, they need to be placed in a common place all activities can use: the application class. Create a custom application class that contains an AppContainer instance.

// Custom Application class that needs to be specified

// in the AndroidManifest.xml file

class MyApplication : Application() {

// Instance of AppContainer that will be used by all the Activities of the app

val appContainer = AppContainer()

}

Note: AppContainer is just a regular class with a unique instance shared across the app placed in your application class. However, AppContainer is not following the singleton pattern; in Kotlin, it’s not an object, and in Java, it’s not accessed with the typical Singleton.getInstance() method.

Now you can get the instance of the AppContainer from the application and obtain the shared of UserRepository instance:

class LoginActivity: Activity() {

private lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Gets userRepository from the instance of AppContainer in Application

val appContainer = (application as MyApplication).appContainer

loginViewModel = LoginViewModel(appContainer.userRepository)

}

}

In this way, you don’t have a singleton UserRepository. Instead, you have an AppContainer shared across all activities that contains objects from the graph and creates instances of those objects that other classes can consume.

If LoginViewModel is needed in more places in the application, having a centralized place where you create instances of LoginViewModel makes sense. You can move the creation of LoginViewModel to the container and provide new objects of that type with a factory. The code for a LoginViewModelFactory looks like this:

// Definition of a Factory interface with a function to create objects of a type

interface Factory { fun create(): T}

// Factory for LoginViewModel.

// Since LoginViewModel depends on UserRepository, in order to create instances of

// LoginViewModel, you need an instance of UserRepository that you pass as a parameter.

class LoginViewModelFactory(private val userRepository: UserRepository) : Factory {

override fun create(): LoginViewModel {

return LoginViewModel(userRepository)

}

}

You can include the LoginViewModelFactory in the AppContainer and make the LoginActivity consume it:

// AppContainer can now provide instances of LoginViewModel with LoginViewModelFactory

class AppContainer {

...

val userRepository = UserRepository(localDataSource, remoteDataSource)

val loginViewModelFactory = LoginViewModelFactory(userRepository)

}

class LoginActivity: Activity() {

private lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Gets LoginViewModelFactory from the application instance of AppContainer

// to create a new LoginViewModel instance

val appContainer = (application as MyApplication).appContainer

loginViewModel = appContainer.loginViewModelFactory.create()

}

}

This approach is better than the previous one, but there are still some challenges to consider:

-

You have to manage

AppContaineryourself, creating instances for all dependencies by hand. -

There is still a lot of boilerplate code. You need to create factories or parameters by hand depending on whether you want to reuse an object or not.

Managing dependencies in application flows

AppContainer gets complicated when you want to include more functionality in the project. When your app becomes larger and you start introducing different feature flows, there are even more problems that arise:

-

When you have different flows, you might want objects to just live in the scope of that flow. For example, when creating

LoginUserData(that might consist of the username and password used only in the login flow) you don’t want to persist data from an old login flow from a different user. You want a new instance for every new flow. You can achieve that by creatingFlowContainerobjects inside theAppContaineras demonstrated in the next code example. -

Optimizing the application graph and flow containers can also be difficult. You need to remember to delete instances that you don’t need, depending on the flow you’re in.

Imagine you have a login flow that consists of one activity (LoginActivity) and multiple fragments (LoginUsernameFragment and LoginPasswordFragment). These views want to:

-

Access the same

LoginUserDatainstance that needs to be shared until the login flow finishes. -

Create a new instance of

LoginUserDatawhen the flow starts again.

You can achieve that with a login flow container. This container needs to be created when the login flow starts and removed from memory when the flow ends.

Let’s add a LoginContainer to the example code. You want to be able to create multiple instances of LoginContainer in the app, so instead of making it a singleton, make it a class with the dependencies the login flow needs from the AppContainer.

class LoginContainer(val userRepository: UserRepository) {

val loginData = LoginUserData()

val loginViewModelFactory = LoginViewModelFactory(userRepository)

}

// AppContainer contains LoginContainer now

class AppContainer {

...

val userRepository = UserRepository(localDataSource, remoteDataSource)

// LoginContainer will be null when the user is NOT in the login flow

var loginContainer: LoginContainer? = null

}

Once you have a container specific to a flow, you have to decide when to create and delete the container instance. Because your login flow is self-contained in an activity (LoginActivity), the activity is the one managing the lifecycle of that container. LoginActivity can create the instance in onCreate() and delete it in onDestroy().

class LoginActivity: Activity() {

private lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel

private lateinit var loginData: LoginUserData

private lateinit var appContainer: AppContainer

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

appContainer = (application as MyApplication).appContainer

// Login flow has started. Populate loginContainer in AppContainer

appContainer.loginContainer = LoginContainer(appContainer.userRepository)

loginViewModel = appContainer.loginContainer.loginViewModelFactory.create()

loginData = appContainer.loginContainer.loginData

}

override fun onDestroy() {

// Login flow is finishing

// Removing the instance of loginContainer in the AppContainer

appContainer.loginContainer = null super.onDestroy()

}

}

Like LoginActivity, login fragments can access the LoginContainer from AppContainer and use the shared LoginUserData instance.

Because in this case you’re dealing with view lifecycle logic, using lifecycle observation makes sense.

Note: If you need the container to survive configuration changes, follow the Saving UI States guide. You need to handle it the same way you handle process death; otherwise, your app might lose state on devices with less memory.

Conclusion

Dependency injection is a good technique for creating scalable and testable Android apps. Use containers as a way to share instances of classes in different parts of your app and as a centralized place to create instances of classes using factories.

When your application gets larger, you will start seeing that you write a lot of boilerplate code (such as factories), which can be error-prone. You also have to manage the scope and lifecycle of the containers yourself, optimizing and discarding containers that are no longer needed in order to free up memory. Doing this incorrectly can lead to subtle bugs and memory leaks in your app.

On the next page, you’ll learn how you can use Dagger to automate this process and generate the same code you would have written by hand otherwise.